I first met Mirko Romanelli at the Framebuilding Festival in Argenta. Within moments of seeing his creations, I was captivated. Pantographed lugs bearing wheat ears, a tribute to his agricultural roots and carefully considered touches that spoke of both engineering and passion.

Born in Seregno, in the Brianza region of northern Italy, to parents who had migrated from the south for work, Mirko now calls Figino home, enjoying its greenery and tranquility away from urban chaos. Trained as a mechanical engineer, his professional path took him through industrial automation design across various sectors, from automotive to his current field in packaging.

His childhood was humble but formative. While studying, he worked countless odd jobs: cleaning woodworking presses, washing hair at a salon for just €20 a week, installing Christmas decorations on wobbly lifts despite his fear of heights, and setting up runways for Fashion Week shows. These early experiences instilled in him a work ethic and resourcefulness that would later define his approach to framebuilding.

Mirko’s first memory with bicycles reveals the maker’s spirit that was present even in childhood. He had an old BMX recovered from an acquaintance—a bit of a wreck, but one he loved dearly. With nothing but pliers, a pipe wrench, a 10mm wrench, and a few Allen keys, young Mirko would spend afternoons taking it apart and reassembling it with parts recovered from flea markets, developing ingenuity through limitation.

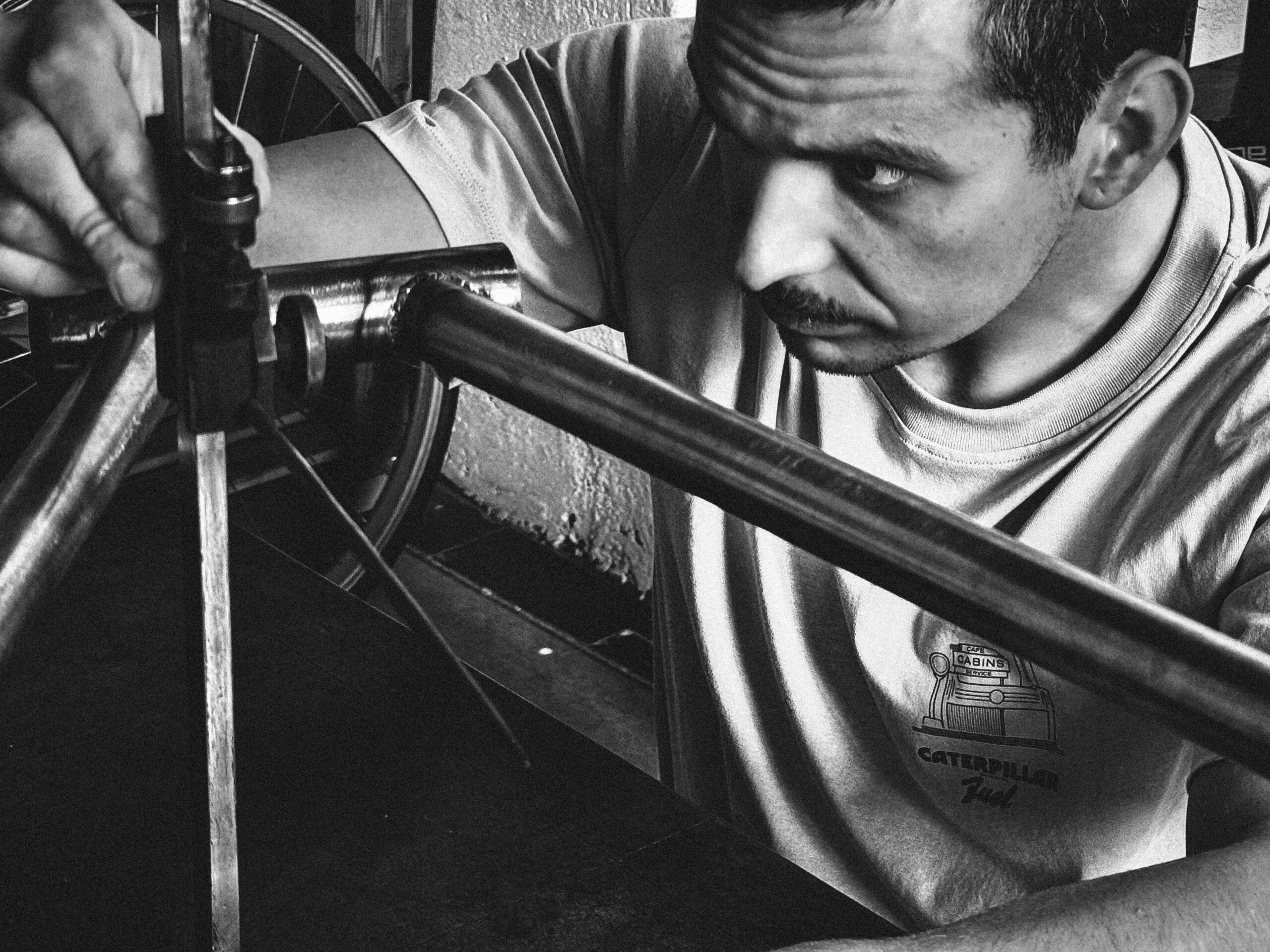

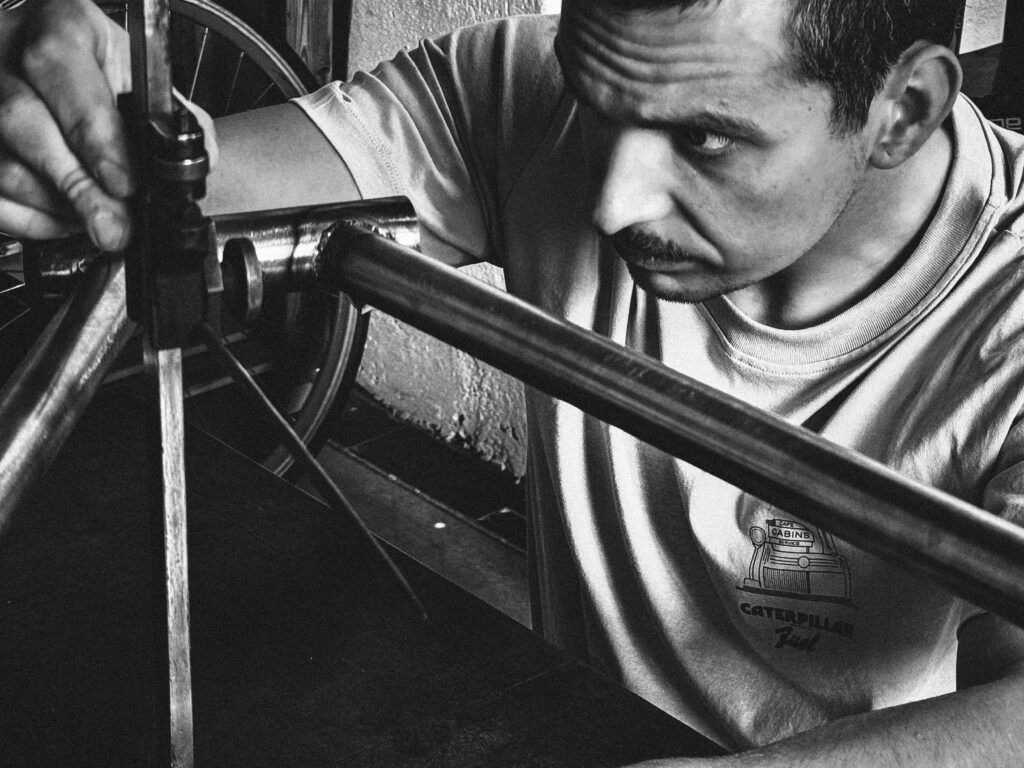

The pivotal moment in Romanelli’s journey toward framebuilding came in 2019, through what he humorously calls “all Bruna’s fault.” Wanting to travel by bicycle with his dog Bruna, he designed a mini cargo bike with touring geometry. When he sought help building it, he encountered Simone D’urbino, a talented young framebuilder in Milan. What was meant to be just one frame became an apprenticeship and passion. After work, Mirko would drive from Como to D’urbino’s workshop near the Vigorelli velodrome, where he learned the basics of brazing steel frames with brass.

Watching wasn’t enough; Mirko needed to work with his own hands. He rented an old, unheated warehouse in his city and continued practicing, completing the bicycle for Bruna. Though the dream of traveling with Bruna never materialized (she was too frightened of the bicycle), a new dream was born: Romanelli Cicli.

With characteristic enthusiasm, Mirko approached his new craft holistically. He immediately collaborated with a graphic designer friend to develop his brand identity. Drawn to lugged bicycles, he created personal pantographs for his works—distinctive signatures of the framebuilder, harking back to an almost forgotten era of craftsmanship. The wheat ear pantograph on his dropouts stands as a tribute to his farming grandparents and parents, symbolizing his origins, blood, land, and hard work.

"If you're a framebuilder without pedaling, you're a welder, not a framebuilder."

As a methodical engineer, Mirko spent evenings doing CAD studies and creating Excel spreadsheets comparing measurements with major brands. He tested bicycles with different geometries to understand their nuances. Though framebuilding remains a passion rather than his primary occupation, he has developed track, road, touring, gravel, and trail models, striving to satisfy any need—with a particular fondness for touring frames and long-distance bikes.

Romanelli’s approach to technique is comprehensive and humble. Beginning with lugged bikes, he moved to fillet brazing and is now studying TIG welding. He believes a true framebuilder should master all three techniques while remaining open to future innovations. While opposed to full carbon, he doesn’t rule out experimenting with structural carbon parts, reflecting his philosophy that a framebuilder’s skill lies in recognizing and applying the strengths of different methods.

For Mirko, the craft’s beauty lies in using his hands—”the best tools we can use are right there at hand.” He finds himself moved when he stops to contemplate what his hands have created, comparing it to the feeling of pausing during a mountain hike to take in the view.

Every bicycle Romanelli builds represents a milestone. Without a structured company or team behind him, each frame requires tremendous effort—running between the workshop, suppliers, graphic designers, painters, and treatment specialists. Yet all this effort “magically disappears when you see the eyes of the person for whom you’ve built their bike.”

Romanelli stays connected to both national and international framebuilding communities, drawing inspiration from talents worldwide. He appreciates builders like Tomii (Texas), Bishop (Maryland), Kirk (Bozeman), Rizzo (Madrid), Chapman (Rhode Island), Fern (Berlin), and Cyfac (France). Among Italians, his influences include Cicli Barco, Stelbel, Ferremi, Pegoretti, Legor, Groucho, Frasca, Bressan, Galletti, and Ottotubi.

What sets an artisanal frame apart from an industrial one? For Mirko, it’s uniqueness. “The artisanal frame is not for everyone,” he explains, not referring to cost but to the mental effort required: the ability to imagine. A custom-made bicycle becomes a legacy—an icon and a romantic passing of the torch that future generations will appreciate, much like finding a grandfather’s bicycle in the cellar.

On steel, Romanelli is pragmatic yet passionate. While acknowledging modern tube sets allow for building frames with competitive weights, he personally doesn’t “give a damn about weight.” He prefers reliability beneath his seat—a bicycle that will bring him home, that doesn’t have an expiration date, that isn’t disposable. To those fixated on weight, he offers blunt advice: “Think about your diet before your bike’s diet.”

The craft has transformed his relationship with bicycles. Where once he thought one bike could do everything, he now appreciates the specific geometries each activity requires. He builds the first of each model for himself, using them as test beds for refinement and upgrades. He believes every framebuilder should have experience pedaling their creations: “If you’re a framebuilder without pedaling, you’re a welder, not a framebuilder.”

Though versatile in his builds, Romanelli holds a special affection for touring bicycles—”intelligent bicycles” with comfortable geometry, simple mechanics, ample attachment points, and generous tire clearance. He describes the “armchair effect” of a well-designed touring bike—feeling so comfortable during long journeys that the bicycle seems an extension of yourself, “perfectly at ease, it will take care of you and take you to your destination as if the bike were alive.”

For Mirko, cycling isn’t about performance but emotion. Performance should only be a consequence. Rather than competing with others, he challenges himself, evident in his solo bicycle trips testing his limits. His most intense cycling emotion came after a personal disappointment, when he rode alone to Santa Maria di Leuca in Puglia in twelve days. On the final day, he “cried with joy throughout the final leg,” understanding “how strong we can be in distress.”

Perhaps the most beautiful lesson framebuilding has taught Romanelli is patience, something he admits lacking in life. The craft’s methodical phases and technical times forced him to slow down, becoming “almost therapeutic.” Today, he’s “much more zen thanks to this passion.”

His advice to aspiring framebuilders is candid: it’s demanding work that requires determination, time, and patience. You’ll “break your hands from continuously filing welds with sandpaper,” miss things outside the workshop, spend money on equipment, breathe unhealthy substances, and likely not make much money. But for those with genuine passion, these challenges are part of the journey.

Looking ahead, after years of personal and professional upheaval, Romanelli’s primary goal is finding tranquility. In framebuilding, he hopes to reach more international markets, perhaps through trade fairs, bringing attention back to Italian craftsmanship, ideally through collective effort among Italian framebuilders without envy or competition.

Romanelli closes with a reflection on sustainability, informed by his experience in the automotive industry. He believes bicycles offer a solution to our environmental challenges, hoping for more bikeable cities, safer connections, and a shift in mentality taught from an early age. In his view, a framebuilder’s role extends beyond building bicycles to promoting their use and embracing a philosophy that contributes to positive change.

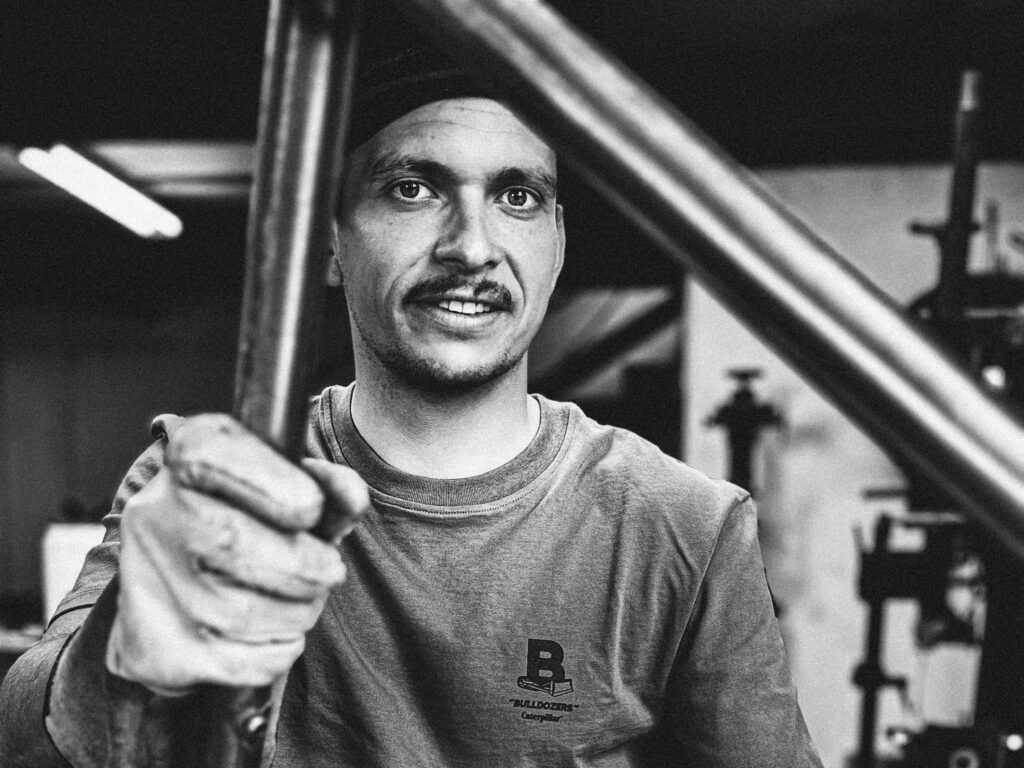

Above: Mirko and me at the Argenta event.

Below: Stefano Gualandri, fellow judge alongside me, and Enrico Biavati presenting Mirko with a medal, symbolizing Stefano’s favorite frame builder.